I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Ecclesiastes

9:11

Spectric School of Poetry

In the early 20th century modernist poetic schools sprang up like toadstools after rain: the Imagists, the Vorticists, the Futurists, the Chorists and whatnot. The sponsors of these schools wrote nonsensical verses and produced pretentious theories to make their junk look like an important contribution to literature. Indignant with these "apes prancing in the Temple", two poets, Witter Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke, contemplated a hilarious joke. They decided to found a new poetic school as a spoof.

In February, 1916, in ten days, from ten quarts of Scotch they extracted a volume of deliberately foolish verses. They titled their book "Spectra" and accompanied it by a pseudo-scientific preface, describing Spectric School of Poetry. Here is an excerpt from the preface (the reader may wish to compare it with a serious modernist theory):

"Spectric" has ... three separate but closely related meanings. In the first place, it speaks, to the mind, of that process of diffraction by which are disarticulated the several colored and other rays of which light is composed. It indicates our feeling that the theme of a poem is to be regarded as a prism, upon which the colorless white light of infinite existence falls and is broken up into glowing, beautiful, and intelligible hues. In its second sense, the term Spectric relates to the reflex vibrations of physical sight, and suggests the luminous appearance which is seen after exposure of the eye to intense light, and, by analogy, the after-colors of the poet's initial vision. In its third sense, Spectric connotes the overtones, adumbrations, or spectres which for the poet haunt all objects both of the seen and the unseen world,- those shadowy projections, sometimes grotesque, which, hovering around the real, give to the real its full ideal significance and its poetic worth. These spectres are the manifold spell and true essence of objects, - like the magic that would inevitably encircle a mirror from the hand of Helen of Troy.

Bynner took Emanuael Morgan for a name, while Ficke chose Anne Knish. Here is a typical example of Emanuel Morgan's poetry:

HOW terrible to entertain a lunatic!

To keep his earnestness from coming close!

A Madagascar land-crab once

Lifted blue claws at me

And rattled long black eyes

That would have got me

Had I not been gay.

And this one is from Anne Knish:

HE'S the remnant of a suit that has been drowned;

That's what decided me," said Clarice.

"And so I married him.

I really wanted a merman;

And this slimy quality in him

Won me.

No one forbade the banns.

Ergo - will you love me?"

The book immediately became popular among advanced poets and critics. Literary journals solicited poetry from Morgan and Knish. A book titled The Young Idea: An anthology of opinion concerning the spirit and aims of contemporary American literature dedicated several pages to Spectrism. As the demand for the Spectric poetry grew, Bynner and Ficke were joined by Marjorie Allen Seiffert who wrote under the name of Elijah Hay. The list of the hoaxed included many important poets and critics: Edgar Lee Masters, Harriet Monroe, Alfred Kreymborg, William Marion Reedy, William Carlos Williams, John Gould Fletcher, and Amy Lowell. And what about you? Are you able to tell true masterpieces of modernist poetry from Spectric parodies? Take this quiz to find out.

The hoax hung in balance ever since the beginning. The editor of the New Republic, who was visiting Mr. Bynner, noticed the proofs of Spectra on his desk. Mr. Bynner thought he was caught, but recovered and said that this was an advance copy of a book a publisher sent him for a comment. The editor became interested and commisioned from Mr. Bynner a review of the book. The quotation I started the essay with is from that review. As time went on, people started to suspect that Morgan, Knish, and Hay were not only spectric, but also spectral. Though many were in correspondence with the Spectrists, no one had actually met them. Various gossips about the true identity of the Spectrist circulated in the society. In April of 1918 Witter Bynner was giving a public lecture, when he was challenged by a man who asked "Is it not true, Mr. Bynner, that you are Emanuel Morgan and that Arthur Davison Ficke is Anne Knish?" Mr. Bynner answered "Yes."

Mikhail Simkin

September 15, 2006

The Hoaxed

The list of folks taken in by the Spectra hoax included many poets, critics and editors, whose names were big at the time.

|

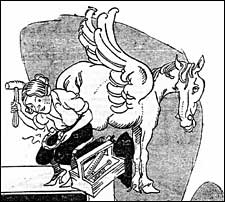

Harriet Monroe accepted five new poems by Morgan and one by Hay for publication in Poetry: a Magazine of Verse. However, soon after that the hoax was exposed. Miss Monroe did not stand by her editorial judgement and refused to print the poems. On the left: Contemporary cartoon, showing Harriet Monroe shoeing Pegassus. |

|

William Marion Reedy praised Spectrism in his journal Reedy's Mirror. On the left: The cover of a book about William Marion Reedy, titled The Man in the Mirror. |

|

William Carlos Williams wrote letters to Elijah Hay. On the left: The cover of a book about William Carlos Williams, titled A New World Naked. |

|

John Gould Fletcher spoke of the Spectrists' "vividly memorable lines." On the left: The cover of a book about John Gould Fletcher, titled Fierce Solitude. |

|

Alfred Kreymborg dedicated the whole issue of his Others: A Magazine of the New Verse to Spectric School. Click here for the complete text. On the left: The title page of that issue. |

|

|

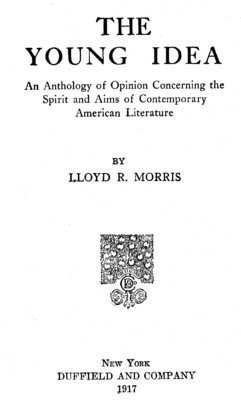

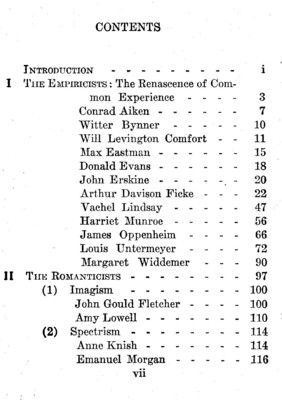

In the Contents of the anthology of opinion on modern poetry, titled The Young Idea, the name of Anne Knish appeared next to that of Amy Lowell ("the fair Trotstky of the Imagist revolution"). The book treated Spectrism (a spoof poetic school) and Imagism (a real poetic school) on equal footing. Here is an excerpt from the book discussing similarities and differencies between Spectrism and Imagism:

I shall be reproached, I fear, for terming the representatives of Imagism and of Spectrism Romanticists. On the one hand, Miss Knish assures us that the doctrines of the Spectric school, of which her collaborator, Mr. Morgan, is the founder, are a fresh interpretation of classic gospels. On the other hand, we have been assured that the reforms which the Imagists are trying to work in our poetry have as their object principles which ,"are the essentials of all great poetry." But to be essentially romantic, a work of art need discover to us no new methods and no new idiom. If through old methods long forgotten and an old idiom it tricks our emotions into responding to a new experience, it has accomplished an essentially romantic result. So that, whether the principles of Imagism and of Spectrism are new or not, we are privileged to call the poetry in which they have found expression romantic art, if for no other reason than that it has, judging by its reception, produced an emotional reaction of romantic quality in its readers.But there is a further reason that we can urge in justification, and that is that these two schools are preoccupied chiefly with promulgating a new technique. Imagism and Spectrism are admittedly programmes of revolt in the field of expression.

The singular fact in the existence of these two schools is that their fundamental objects are directly antithetical. Imagists proclaim their faith in a rendering of an exact picture in an idiom which combines the characteristics of suggestion, vividness, concentration, and externality, in either of two forms, free verse or polyphonic prose. The Spectrists have as their objects the diffraction of emotion, and the conveying of after-images and overtones; moreover, they employ both the traditional poetic forms and free verse. The Spectrists thus seem, in a measure, to be chiefly interested in blurring and encircling with a haze of symbols the image wich the Imagists, in their poems, are anxious to convey with photographic precision.

This is not the place to further elucidate the theories of these two schools of writers. Readers who wish for more light are referred to the preface to "Some Imagist Poets," and to Miss Amy Lowell's article, "A Consideration of Modern Poetry" in The North American Review for January, 1917, and to the preface to "Spectra" by Miss Knish and Mr. Morgan. It is interesting to note, however, that the poetry of both these schools emphasizes, each in its own way, a point touched upon in the contribution of Miss Harriet Munroe, the contrast between man's littleness and the greatness of the universe and the fantastic and ironic self-importance of man in his relation to the universe.

And here is the part of The Young Idea dedicated exclusively to Spectrism:

The latest of the movements for a wider technical freedom in poetry is that brought forward by the Spectrists, a school for which Miss Anne Knish and Mr. Emanuel Morgan stand as sponsors. Miss Knish defines its aim as a fresh interpretation of classic gospels. She believes our present poetic renascence to be a derivation from a stale current.

I do not know if I have a right to speak on this subject, for American poets will resent, perhaps, the criticism of one whose native tongue is the Russian, and who has written only one English book. Yet since you ask me, I will answer, with humility, as to poetry only.

Your new movement in poetry seems to me too closely derived from a French movement that is already ancient history to Continental Europe. Young people without genius slip into this stale current and have much fun; but many of their tragic poems are of humorous effect, I think, and when they would be funny I sometimes weep. It is like a piece of cheese left over at breakfast. So little is basically grounded on a theory of Tsthetic that is of new import; and these young people fear the classic aesthetic as they would poison. They need not; though we seek new drinks to become drunken with, the doctrine of Aristoteles remains the staff of life, the bread.

We who are of the Spectric School of poets have tried, contradicting no ancient truth, to give fresh interpretation to classic gospels. If our Tsthetic dogma be sound, the other poets will before long become aware. But these are in American poetry days only of beginning; and I think these people know nothing of European literary history who speak so much of "new, new, new!"

Mr. Emanuel Morgan, collaborator with Miss Knish upon "Spectra," tells us that the essential quality of Spectric poetry is humor, and defines its basis in vision.

Yes, there is a new, or, rather, renewed movement in poetry. Its ideals are life. It is born of the death of the immediate past. Its most important current, for the moment, seems to me to be the current of mirth, and in that current much of our work belongs. We call ourselves a "School." But all we are doing, as I see it, is to combine! and realize qualities which are appearing, now here, now there, among much modern poetry not professedly spectrist, viz.: catholicity of subject and metre, a quick registering of mental reflections by a sort of leapfrog metaphor, an exchange of intuitions; in short, by imagination or humor, a breaking through the mere pretty or ugly surface of things.

In our own convenient terms, spectrism belongs, to its time in that it intends the poem or spectrum, by means of laughter or other illumination, to send an enchanted X-ray through the skin to the lungs and liver and heart of life.

Consulted Sources

- Anne Knish and Emanuel Morgan, Spectra (Mitchell Kennelly, New York, 1916) Click here for the complete text of the book.

- Others: A Magazine of the New Verse, Vol. 3, No. 5, January, 1917 (The special issue dedicated to Spectrism) Click here for the complete text of the journal.

- Lloyd R. Morris, The Young Idea (Duffield and Company, New York, 1917)

- William Jay Smith, The Spectra Hoax (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connecticut, 1961)

Spectric School of Poetry is the fifth essay in the Ecclesiastes 9:11 series. To be posted of our future releases subscribe to our newsletter.